As we move to the work on the Mid-Barataria Diversion many efforts are showing our past and future.

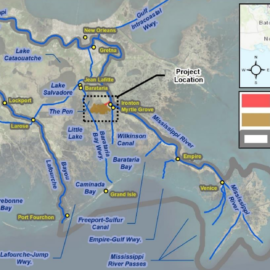

The willow trees and cutgrass emerging from the muck in this swampy stretch of St. Charles Parish west of the Mississippi River are in some ways Louisiana’s past brought back to life. They could also be its future. “Imagine what we could do when we start really targeting this and trying to figure it out,” Theryn Henkel, a scientist with the state’s Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority, said after she pulled a soil sample showing new land had been built. The structure known as the Davis Pond Freshwater Diversion has been open for a couple decades, but it is receiving renewed attention because of the lessons it may hold about major plans on the horizon aiming to slow the disappearance of Louisiana’s coast. State officials are moving steadily toward construction, expected later this year, on an unprecedented project that could essentially turn back time. Called the Mid-Barataria Sediment Diversion, it will channel muddy water from the Mississippi River into Barataria Basin, mimicking the processes that built south Louisiana long before anyone dreamed of throwing beads, cups or coconuts here. It is expected to cost more than $2 billion, paid for with settlement proceeds from the 2010 BP Deepwater Horizon oil spill. A similar project on the east bank of the river, called the Mid-Breton Sediment Diversion, is being planned for the years ahead.

nola.com

There is a difference in the existing diversion and the proposed one but lessons can be learned.

Both will dwarf the Davis Pond diversion, and both are being designed with a different purpose in mind. But still, elements of that older project portend some of what likely lies ahead. For state officials and scientists who recently carried out an in-depth study, Davis Pond shows the river’s land-building capabilities and potential to slow the erosion steadily peeling away Louisiana’s coast. “There are trees there now where there weren’t before,” CPRA executive director Bren Haase said. “All of that is just an affirmation that the river has the power to do some really good things if we let it go and let it do its thing.” But while the state has presented reams of scientific data to support Mid-Barataria, the project does not have unanimous backing. Many in the state’s seafood industries warn it will wipe them out. Others say the project’s astronomical cost and untested nature make it too risky. What’s clear is that big change – possibly even historic change – seems on the way for parts of coastal Louisiana.

Built in 2002 Davis Pond was the worlds largest diversion.

Though it has since been far surpassed, Davis Pond was labeled the world’s largest freshwater diversion when the Army Corps of Engineers completed it in 2002, at a cost of around $120 million. It funnels Mississippi River water down a 2.2-mile channel into the diversion area about 15 miles upriver from New Orleans, northwest of Lake Cataouatche. Like its older cousin, the Caernarvon Freshwater Diversion on the river’s east bank in Plaquemines Parish, Davis Pond was not primarily designed to build land, though that was a hoped-for benefit. Its purpose was to reduce salinity in the Barataria estuary due to saltwater intrusion, helping species such as oysters. Though it opened two decades ago, Davis Pond was not fully operational until 2009. Since then, there have been concerns over the results. One study in 2019 found that both Davis Pond and Caernarvon caused more erosion than restoration. However, a more recent study rebutted the earlier one, arguing that data had been misused and arriving at a sharply different conclusion. It said that Davis Pond had built 1.32 square miles of new land over the last couple decades, while no statistically significant change was noted for Caernarvon. “It didn’t make any sense to me because the airboat kept getting stuck when we were out there in 2018,” John White, an LSU professor and one of the study’s authors, said of the new land they found and documented with the help of around 150 sampling stations employed 11 years apart, among other methods.

The new reports were good news.

State officials interpreted the recent study as good news, especially considering neither of those diversions were built specifically to build land. For that reason, there are key differences between them and the two planned diversions. The most obvious difference is size. Davis Pond is capable of diverting up to 10,650 cubic feet per second, or about 4.8 million gallons per minute. Mid-Barataria, to be located downriver of New Orleans in Plaquemines Parish, will be capable of diverting up to 75,000 cubic feet per second, though it will operate at various capacities throughout the year. Another important difference is that Mid-Barataria will be designed to draw from the river’s deeper, sediment-rich stretches. Davis Pond pulls from higher in the water column, where there is less sediment, according to state officials. Mid-Barataria is projected to build around 21 square miles of land by 2070, with sea-level rise, erosion and subsidence taken into account.

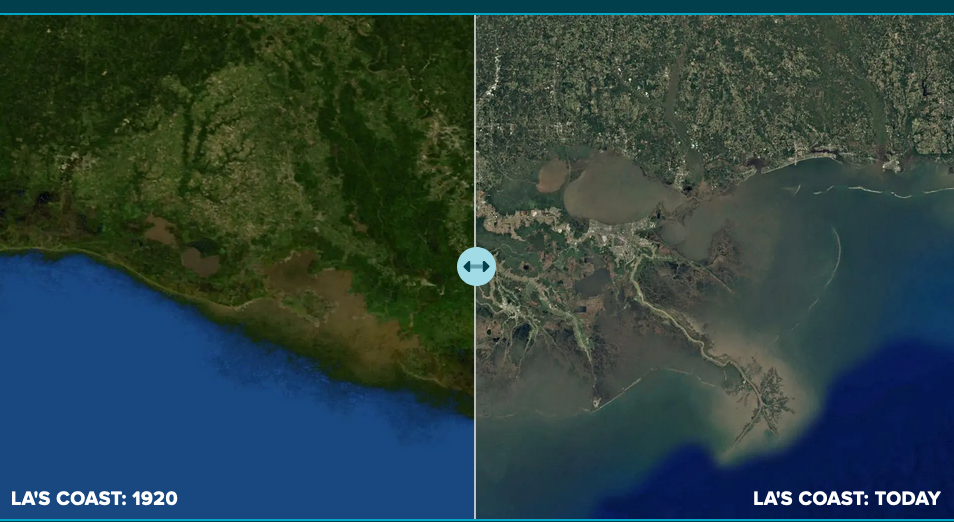

Land loss is driving land construction.

To understand why the state is pursuing such an ambitious plan, it’s important to consider the forces destroying Louisiana’s coast. More than 2,000 square miles of land have been lost since 1932 – about the size of Delaware. Before the construction of the Mississippi’s levees, the river meandered across various locations, depositing sediment and building land. Keeping the river hemmed in has robbed the coast of sediment, allowing erosion and natural subsidence to eat away at it. The multitude of canals cut through marsh by the oil and gas industry have also taken a toll, while sea-level rise exacerbated by climate change is threatening to inundate large parts of the coast in the years ahead. For state officials, more permanent solutions must be found in addition to the marsh rebuilding projects carried out annually since those, too, gradually erode. They recognize that it is impossible to restore the coast to what it was, and aim instead to work toward a sustainable delta. The fight over the diversions will nonetheless continue. Commercial fishermen are planning a lawsuit, and a potential candidate for governor, Lt. Gov. Billy Nungesser, the former Plaquemines Parish president, opposes the diversion plans.

No one is looking at this diversion through rose colored glasses.

State officials and the Army Corps of Engineers’ environmental assessment acknowledge fisheries damage, with $378 million being set aside for mitigation on that and other issues. Shrimp and oyster populations in the basin will be hit hard, while recreational fishing for speckled trout and redfish will also be affected. Bottlenose dolphins in the area could be wiped out. Commercial fishing representatives say asking lifelong shrimpers and oyster fishers to simply pack up and move elsewhere is not an option. They also argue that the amount set aside for mitigation is woefully small. They say more marsh-building projects should be done instead. “That’s going to be a devastating blow to the Barataria estuary,” said Mitch Jurisich, chair of the state’s oyster task force and a lifelong oyster farmer. “What is 21 square miles of land in 50 years going to do for us? Absolutely nothing. It is going to kill off the very industries that survive off of what our estuary has given us.” George Ricks, a charter fishing captain and head of the Save Louisiana Coalition, echoed those concerns, pointing to brown shrimp landings as one example. Citing 2017 dockside figures, he said shrimp landings that year amounted to around $9 million in Barataria Bay alone, a number that he expects to be eliminated. Beyond that, he argues that a part of the state’s culture will be lost. “How do you put a monetary value on a culture and a heritage?” he said.

Doing nothing is not a solution.

Alisha Renfro, a coastal scientist with the National Wildlife Federation, said doing nothing is not a viable option. The river was always changing before levees kept it in place, and the coast will continue to transform, she noted. “What we have today is not the system we’re going to have tomorrow,” she said. “We can either choose to let Mother Nature hand us whatever it’s going to hand us, or we can be proactive and actually restore the system to something that might actually function better for us moving into the future.”

The diversion is the best option and yes there will be bad sides. Change is had,