We knew the air was bad from the refineries but not that they pollute the water.

With roaring flares and stacks that billow clouds of smoke and vapor, it’s no secret that oil refineries harm the air. But the toxic chemicals spilling out of refineries as wastewater also pose environmental risks, especially in Louisiana, where eight facilities ranked among the top oil operations that pollute public waterways, according to a nationwide study. In an analysis of wastewater discharge records from 81 refineries, the Environmental Integrity Project found south Louisiana refineries discharging some of the highest amounts of heavy metals, nitrogen and other pollutants into rivers, estuaries and other waterways. The EIP study says the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and state regulators are doing little to curb the half billion gallons of wastewater that pours from U.S. refineries each day. Federal standards enacted decades ago are rarely enforced and have failed to keep pace with advances in water treatment methods, the study said. “The EPA’s failure to act has exposed public waterways to a witches’ brew of refinery contaminants,” the study said.

nola.com

Environmental Integrity Project

A sad list of who and what they discharge into the water.

The Marathon refinery along the Mississippi River in Garyville ranked fourth and the Phillips 66 refinery in Lake Charles ranked seventh for releases of nickel. Marathon’s refinery ranked 8th for selenium discharges, and the Exxon Mobil refinery in Baton Rouge ranked 10th, the EIP study said. Nickel and selenium are toxic metals that can mutate fish, mangle reproductive systems and travel up the food chain to other sea life, birds and people. They also persist in the environment for long periods, potentially poisoning an ecosystem for decades, EIP Executive Director Eric Schaeffer said. “These heavy metals are highly toxic to fish and other critters even in minute quantities,” said Schaeffer, who managed the EPA’s civil enforcement division during the late 1990s. “In the environment, they’re literally impossible to remove.” The Citgo refinery in Lake Charles, Phillips 66 Alliance Refinery near Belle Chasse, and Chalmette Refinery near New Orleans ranked 8th, 9th and 10th for releases of nitrogen, a nutrient that feeds algal blooms and is the main contributor to the Gulf of Mexico’s low-oxygen ‘dead zone.’ The three refineries released a combined 1.4 million gallons of nitrogen in 2021, according to the study. The Alliance Refinery closed in late 2021 and now serves as a storage terminal. The Exxon Mobile refinery in Baton Rouge and the Shell refinery in Norco ranked sixth and ninth for the release of ‘total dissolved solids,’ a cocktail of byproducts from the refining process that can boost water salinity, harming fish and tainting public water systems.

The bad news continues.

Louisiana made up half of the top 10 ammonia polluters. The Alliance Refinery ranked first, with more than 255,000 lbs. released in 2021. The Valero refinery in Norco, Phillips 66 and Citgo refineries in Lake Charles, and the Chalmette Refinery were also top dischargers of ammonia, which can harm the internal organs of fish and other animals. According to the EIP, the Valero refinery in Norco has outdated federal permits that allow it to dump nearly 2,000 lbs. of ammonia per day into the Mississippi. Most Louisiana refineries named in the study did not respond to requests for comment or deferred questions to oil industry trade groups. The Louisiana Mid-Continent Oil and Gas Association, which represents many of the refineries, did not respond to a request for comment. In a statement, Exxon Mobil said its refineries operate “in compliance with stringent local, state and federal regulations, and are always working to improve environmental performance.”

Improve environmental performance? Right!

Whatever refineries are doing to improve, it’s clearly not enough, said John Beard, founder of the Port Arthur Community Action Network, a group working to clean Sabine Lake and other waterways along the Texas-Louisiana border. “People say we need the jobs and the products (refineries) make,” he said. “That’s true. But we don’t need the pollution. They can do better.” The EIP places much of the blame on the EPA, which it says has the power to toughen refinery regulations and enforcement but chooses not to act. The U.S. Clean Water Act requires the EPA to set limits on refinery pollutants and update them every five years as treatment technology improves. But the EPA has never set limits for several common refinery pollutants, including selenium, benzene, mercury and cyanide, according to the report. And while the tools for treating these pollutants have become better and cheaper over the years, the EPA still holds refineries to standards set nearly 40 years ago. “Nobody thinks a rotary phone is the best way to make a phone call in 2023,” Schaeffer said. The same thinking, he said, should be applied to the EPA’s 1980s-era water treatment standards.

Technology could help but the refineries are old and there is a quistion if the technology would work with the outdated systems.

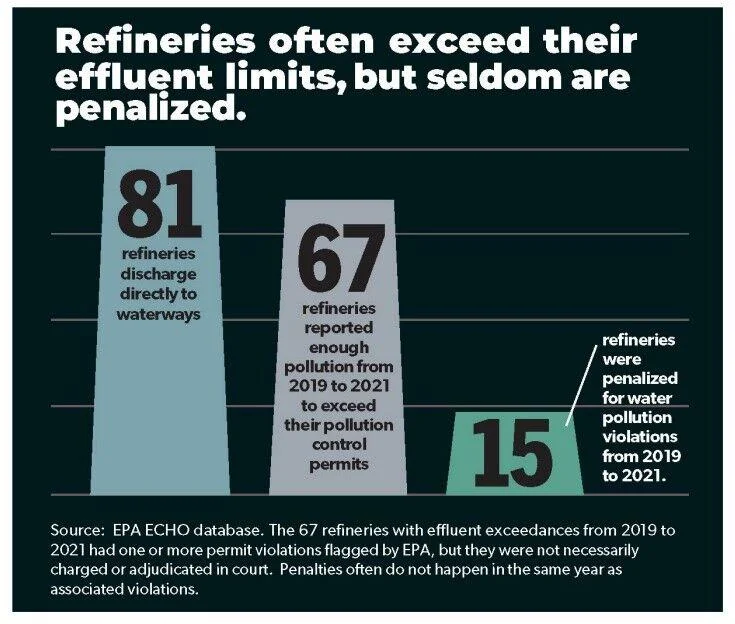

Few refineries have adopted new technology partly because most are very old, averaging 74 years in the U.S. The Exxon Mobil refinery in Baton Rouge started operations in 1909. The Marathon refinery, at almost 50 years old, is one of Louisiana’s youngest. The report says the EPA has a double standard when it comes to coal-fired power plants, which are also typically quite old. In 2015, the EPA mandated tougher coal plant discharge limits for selenium, even though the average refinery discharges far more selenium than the average coal plant, according to the EIP. EPA officials said they were aware of the report but declined to comment on it. When refineries exceed their generous discharge limits, the EPA often fails to act, according to the study. More than 80% of the 81 refineries assessed by the EIP exceeded their pollution limits at least once between 2019 and 2021, but only a quarter were penalized, it said. When the EPA does issue fines, they often amount to “chump change” for the billion-dollar industries, Schaeffer said.

EIP

Some states, California, have taken over from the EPA and enforces standards they set. Louisiana could but I don’t see this in the cards.

In some cases, states have enacted tougher rules than the EPA. California, for example, has limited ammonia discharges from a Valero refinery in that state to about 1% of the ammonia spilling from the Valero refinery in Norco, according to the study. Louisiana rarely enacts stricter rules than the EPA. The state Department of Environmental Quality typically follows the EPA’s lead and has in cases fallen short of it. It has lately taken heat from the federal agency over allowing Black people to suffer disproportionate impacts from air pollution. But the study says the EPA is doing the same to minority and poor communities. Citing the EPA’s own data, the study notes that over half the country’s refineries are concentrated in areas with high percentages of Black or Hispanic residents. Two-thirds of refineries are in areas where the number of low-income residents exceeds the national average.

Once the pollutants get into the water they spread.

Once refinery pollutants are in public waterways, they spread much farther than the neighboring communities, potentially contaminating the beaches where many people swim and the fish many people eat. The report estimates that nearly 70% of the refineries examined in 2021 discharged into a waterway that was listed as “impaired” under the Clean Water Act. That means the water was considered unsafe for for fishing, swimming and other recreational activities. “We’re in the belly of the beast,” Beard said of the heavy industry along the Gulf Coast. “Everything that happens with petrochemicals is happening here.” “Think about that,” he added, “next time you go fishing or swim in the Gulf of Mexico.”

We have made a bargain with the devil as both the air and water are polluted by the industry we courted.