Courtesy of SURA, Inc

An archaeological survey of the site shows unmarked graves.

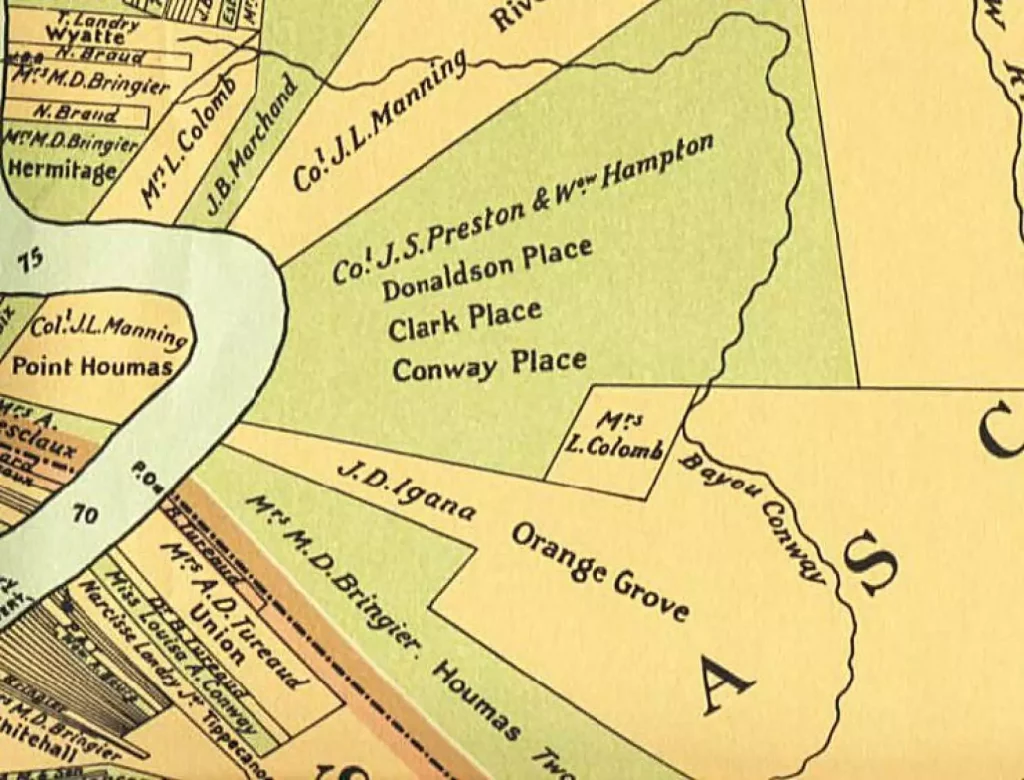

In late 2022, archaeologists with a consulting group spent weeks surveying part of a former plantation in Ascension Parish, where the industrial chemical company Air Products and Chemicals Inc. plans to build a $4.5 billion hydrogen and ammonia complex. A senior archaeologist with infrastructure consulting firm AECOM told the State Historic Preservation Office in an email on Dec. 8 that he found over a dozen square, concrete stones scattered within a few hundred feet of a cemetery that is also on the property. At the time, the archaeologist said they resembled grave markers, with illegible letters and numbers inscribed. Charles “Chip” McGimsey, Louisiana’s state archaeologist, has since gone out to see the markers — though he is not convinced they represent graves. “They’re not anything that looks like any kind of headstone or footstone or anything like that,” said McGimsey. “In fact, to be perfectly honest, I have no idea what they are. They certainly don’t look like anything I’ve seen.” He’s still waiting for the consultant to submit its final report, after the group said it planned to do more research on the stones.

wwno.org

The company of course hears no evil, sees no evil and hides their heads.

Air Products said they have found no evidence of other burial grounds on their site beyond the one studied by their consultant, known as the Orange Grove Cemetery, and have no plans for further investigations. But even if the markers aren’t graves, environmental groups are more concerned there could be unmarked burials for the formerly enslaved on other parts of the 376-acre property — and in Louisiana, there’s no process for ensuring they’re found before a project breaks ground. The concern comes amid a national movement to enhance protections for Black cemeteries after industrial projects ranging from refineries to pipelines have destroyed graves that weren’t previously documented. Air Products’ plant would pull hydrogen from natural gas and capture the carbon left over before it’s released into the atmosphere. From there, the remaining carbon would travel through pipelines before being stored a mile underground beneath Lake Maurepas. The contentious plan has faced enormous pushback from neighboring parishes concerned about the health of the lake and the risks posed by carbon storage. Now, environmental groups, who also oppose the plant, say the problems with the plant could start with its construction. And, to an extent, McGimsey said their concerns over the existence of an unmarked slave burial site is reasonable.

Unmarked graves and even grave yards were not unusual on plantations.

During the antebellum era, he said it was common for plantations to have at least one slave cemetery that was often poorly documented on any maps drawn at the time — which makes them hard to find. “I have no idea where it is. I don’t know how big it is. I don’t know how many people are there,” McGimsey said. “Unfortunately, there is just no practical way to go find them, unless you have some historic clues that can lead you in certain directions.” These historic clues are also called “anomalies,” small areas that can be charted on historical maps and aerial photographs that stand out as strange or transformed over time. Forensic Architecture research fellow Imani Jacqueline Brown said her group documented five anomalies within Air Products’ footprint during their 2021 investigation into possible slave cemeteries located within Louisiana’s petrochemical corridor along the Mississippi River. They include the known cemetery and the location of what may have been a complex that included a sugar mill and slave quarters. The other three anomalies have yet to be investigated. She also criticized the quality of the only other cultural survey completed on the site in 2014, which Air Products has relied on in drafting their own report for federal regulators. The authors of that prior report, working on behalf of petroleum coke exporter Impala Terminals, overlooked the likelihood of a plantation house located close to where the property meets the Mississippi River, as was typical during the antebellum period. Instead, the 2014 report suggested the sugar mill site would have also been the location of the “big house.” “It raises questions about the value of prior surveys that have been conducted and also reveals some of the kind of trappings of these types of surveys when they’re not done carefully and by people with real knowledge of this history,” Brown said.

The only thing to do is an extensive search for graves.

She said the only way to be certain that no historic structures, let alone possible cemeteries, are destroyed would be to do a thorough ground survey across the entire site — something that McGimsey said is not required by state or federal law. “All the law says is you can’t disturb the cemetery. You know, as long as you know where the graves are,” he said. And even then, the two major laws protecting graves — Louisiana Unmarked Human Burial Sites Preservation Act and the federal National Historic Preservation Act — allow companies to build right up next to cemeteries, though McGimsey’s office tries to require at least a small buffer. Air Products’ draft design for its facility would have the plant built directly beside the cemetery that has already been fenced off, according to its state air permit application. An Air Products spokesman said the company plans to keep the cemetery open for visits, provide a 100-foot buffer and add sound protection to diffuse plant noise. McGimsey also said requiring companies to survey hundreds of acres is not practical. He said remote sensing — or ground penetrating radar — would be the simplest way, which involves walking with a wheeled device that resembles a push lawnmower. “With some companies (having) acquired a thousand acres, you can’t reasonably expect them to have a person walking with a ground penetrating radar, over all of that ground,” he said.

This is a yes, but issue.

The radar is not always a reliable way to find graves, especially in Louisiana, where the ground can be too moist, said University of New Orleans archaeologist Ryan Gray. It can also be difficult to roll the sensor over a plowed sugarcane field. “You can use it and sometimes you can see things with it, but it’s not 100%,” he said. Gray said absolute certainty only comes by stripping off the top layer of soil to check for grave shafts -– or holes dug to lower coffins.

This is the history of plantations and we should preserve all aspects of it.