I love my gas stove. I love the conveniences of gas that comes on then off instantly. But, is it good for the environment?

Darrell LeBlanc shovels ice onto a shrimp boat, the marsh buffering the Gulf of Mexico behind him, a scene that’s played out countless times along the Louisiana coast over much of the state’s history. But the backdrop on the horizon, a giant tangle of cranes and storage tanks, is unmistakably modern. “All that was open,” said the 60-year-old who has spent his life around the commercial fishing industry in Louisiana’s southwestern corner. “Cameron’s changed like day and night to me.” The construction site on the edge of the Gulf in Cameron Parish is a monument to Louisiana’s embrace of the liquefied natural gas industry, which now exports around the world from here. LNG has been touted as an important bridge fuel that burns far cleaner than coal, helping wean developing nations away from the dirtiest sources of electricity as the world gradually moves toward renewable energy.

theadvocate.com

It will be a long haul to get way from oil. We will need to take steps that are not directly on the way but will get us there eventually. We have those who say change now and others who say over my dead body. If we don’t change there will be dead bodies!

But LNG is also an important source of greenhouse gas emissions, and some question if the trade-off in pollution and major tax breaks amounts to a good investment for the state. The industry will surely factor into discussions as world leaders gather for a climate summit this week in Scotland, a meeting that Gov. John Bel Edwards will also attend. At the same time, Lake Charles will host a major LNG industry conference from Tuesday through Thursday. With two huge LNG export facilities up and running, both in Cameron Parish, Louisiana now has the highest output capacity in the country, with more on the way. Cameron Parish Port Director Clair Hebert Marceaux has frequently described the industry in these terms: If the parish were a country, it would be the world’s third-largest LNG exporter after Qatar and Australia. Edwards, who will leave office in two years, has convened a task force to come up with a plan to reduce emissions of climate-altering greenhouse gases in a state that relies heavily on the petrochemical and energy industries, which are major sources of pollution. But he nonetheless says oil and gas, including LNG, will continue to play a role. He has promoted the state’s plans for carbon capture and storage technology, which is controversial among environmental activists. “I believe that LNG has a tremendous role to play,” Edwards said Thursday on a visit to the Lake Charles area before his departure to Scotland. “Every time anywhere in the world a coal-powered plant is converted or decommissioned in lieu of a gas-powered plant, natural gas, then that helps the environment.” But he made clear that the state must eventually accept the move away from oil and gas for its energy, noting climate change’s effects on the coast, including rising sea levels and more intense storms. “There’s a transition underway,” Edwards said. “It’s going to take a decade or two or three — I don’t know how long — but the future is not fossil fuels. They’re never going to go away completely. But there’s a cleaner energy future.”

LNG is expensive both in building the plants and then in the distribution of the product.

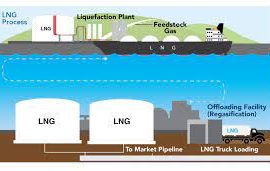

Turning natural gas into a liquid makes it easier to transport. The gas is piped into the plant, supercooled to around minus 260 degrees Fahrenheit, then transferred onto tankers. Facilities in southwest Louisiana were originally intended as import plants, where LNG from other countries would be turned back into gas and used domestically. But following the fracking boom, which greatly increased the U.S. supply of gas, the strategy changed and facilities were geared toward export instead. bic feet last year, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration. Around 55% of that passed through Louisiana’s two export plants, Cameron LNG in Hackberry and the Cheniere plant at Sabine Pass. Additional plants are either being built, seeking approvals or awaiting supply contracts before investors make final decisions on construction along the Louisiana coast, amounting to tens of billions of dollars in potential spending. A project that now appears stalled, at Monkey Island in Cameron Parish, had at one point involved the president’s son, Hunter Biden, the New Yorker magazine reported.

Louisiana is giving tax exemptions, taking the money away from education and medical and social programs, to the companies to draw them here.

Companies can seek to take advantage of Louisiana’s Industrial Tax Exemption Program, which can exempt up to 80% of property taxes for up to a decade. When an exemption was approved for the Driftwood LNG project south of Lake Charles in 2018, it was described as the largest in state history, possibly reaching more than $2 billion over 10 years. Driftwood qualified for a 100% exemption from local property taxes since it began the process before Edwards’ changes to the program took effect and reduced the maximum break to 80%. Southwest Louisiana has proved an attractive location for a range of other factors as well, including its pipeline infrastructure, the availability of natural gas and deep-water access for shipping, said Jim Rock, head of the Lake Charles-based Lake Area Industry Alliance. McNeese State and SOWELA Technical Community College also have programs geared toward such industries. But Rock mentions another factor: For better or worse, the region is accustomed to heavy industry, having long been home to petrochemical plants and offshore energy businesses. It is less likely to face local resistance, he said. The plants can create thousands of temporary jobs in the construction phase, but fewer over the long-term. Marceaux has said that every 10 construction jobs tends to result in roughly one permanent position.

Hiring and jobs are always mentioned in the support of these plants.

While she seeks to promote local hiring, it’s clear many of the construction jobs are filled by non-Louisianans. RV parks dot the parish, filled with out-of-state plates, and white buses ferry workers to and from the construction site for Venture Global LNG, the plant being built near where LeBlanc was shoveling ice. For Rock, the projects are still worthwhile, since the industry “further expands the stability of the economy in southwest Louisiana.” “These plants are the most expensive plants I’ve ever heard of. They’re multibillions of dollars,” he said. “Those plants are going to need to operate for a long time to justify the investment. … It brings good-paying jobs with good benefits that are going to be there for a long time.”

Not everyone is so supportive of the plants. There are a lot of costs that are not factored in the largest being the health costs.

But for Anne Rolfes, director of the Louisiana Bucket Brigade, the life span of the plants is part of the problem. She notes that while natural gas burns cleaner than coal, it’s still an important source of emissions. Liquefying the gas at plants like those in Cameron Parish also emits greenhouse gas. Plants need a large power supply for the process, and some generate their own electricity. A recent study from David Dismukes, who heads LSU’s Center for Energy Studies, ranked Cheniere’s Sabine Pass facility as the No. 3 greenhouse gas emitter among Louisiana industrial sites in 2019. The potential for methane leaks are also an issue. Methane is 25 times more potent than carbon dioxide when it comes to trapping heat in the atmosphere, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

The prevalence and intensity of the recent storms are another strike against these plants.

With southwest Louisiana having been hit by four natural disasters since August 2020, and climate change intensifying storms, Rolfes says the embrace of the industry is misguided. “This idea that we can build facilities that will make that situation worse is just unfathomable,” she said. Rolfes also has concerns regarding the risk of storm damage to facilities and the pollution that could result. The companies involved say the plants are built to withstand such risks. Dismukes agrees that emissions from LNG plants are a problem. He believes carbon capture may help deal with it, though critics of the technology say it brings a new set of concerns, including the potential for leaks. Regulators are also likely to increasingly demand emissions reductions, he said. But regardless, like Edwards, he says natural gas will have to serve as a “bridge fuel” by transitioning developing nations away from coal before an eventual move to renewables. “I just don’t see how we can bring the developing world onboard without having gas as part of that solution,” he said. “And that gas has got to come from somewhere, and this is one of the easiest, best places to get that gas in the near term.”

Despite the cons, the pros will win out at least in the short run.

For now, more construction seems inevitable, furthering the transformation in parts of remote Cameron Parish. Venture Global construction has blocked access to a fishing jetty and boat launch, and lifelong shrimpers like Anthony Theriot worry that he will eventually be cut off from the waters he plies. “As long as they leave the marsh alone, we’re fine,” he said as he worked on his smaller boat last week. But the 46-year-old has also found a way to earn money from the LNG industry, turning land he owned into an RV park for workers. And he says he doesn’t want his kids to follow him into commercial fishing. One of his sons is studying process technology, which could allow him to work at the region’s energy and petrochemical plants.

For the short term it might work but a 40 year plant is not for the short term!